People are always grateful to see representation in media. The representation people seek can depict anything about a person’s identity, whether that’s related to sexuality, ethnicity, disabilities, etc. That being said, I think it’s equally as important to represent more unpleasant things that tie into identity– discrimination.

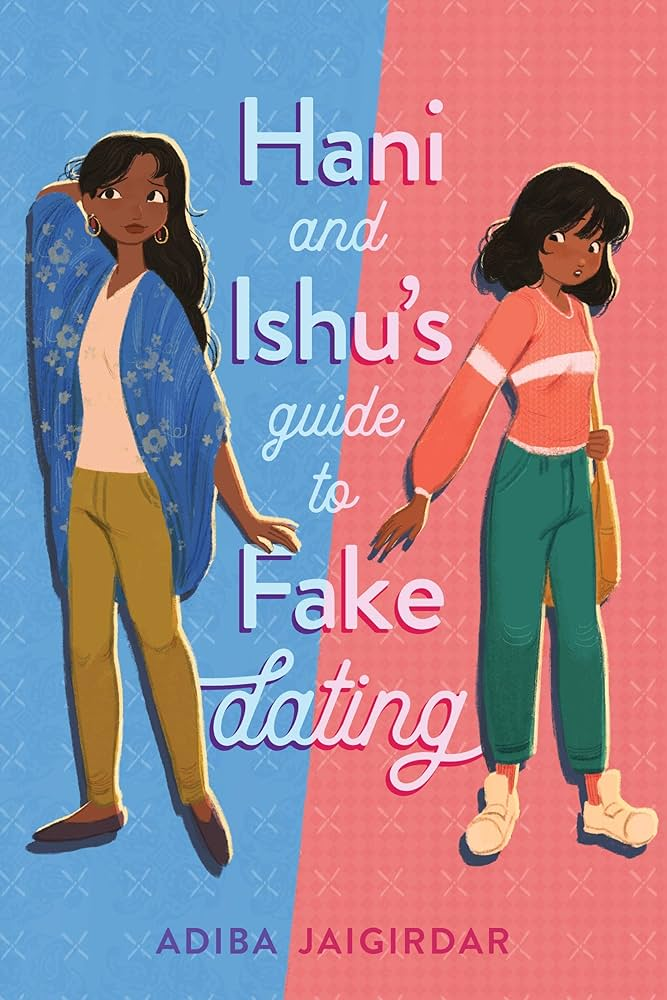

Hani and Ishu’s Guide to Fake Dating was published in 2021 by Adiba Jaigirdar, a Bangladeshi-Irish writer. It follows two girls, Humaira (on the left) and Ishita (on the right), who conjure a plan to “date” in order to gain something in return; Humaira wants her friends to accept that she’s bisexual, and Ishita wants to gain popularity in order to win Head Girl at their school. Though their relationship began as nothing but a plot for their own personal benefit, the girls end up developing feelings for one another and are in a real relationship at the end of the novel. It’s a story about acceptance, growth, and romance, but also about homophobia, toxic relationships, and xenophobia.

In the novel, we are introduced to Humaira’s group of friends– two girls named Aisling and Dee– who are what one could call “sheltered white girls.” In chapter five, they attempt to introduce Humaira to a boy, and, albeit begrudgingly, she gives the boy a chance. At the end of the date, Humaira still finds herself uninterested in the boy and claims this is because “right now, all men seem overwhelmingly attractive” (pg.36). When she tells her friends she’s not interested in boys at the time and eventually that she’s bisexual due to the pressure she’s feeling, her friends react rather poorly.

“Have you even kissed a girl?” Aisling asks.

“No,” I mumble. Unfortunately, I have kissed way too many boys —most of them unpleasant experiences.

“Then how can you say you’re bisexual?” Aisling asks. (p.36)

In this scene, Aisling denies Humaira’s sexuality because of her lack of experience with women, claiming that there’s no way she can be sure if she’s never been with a girl, which eventually leads to Humaira claiming she’s dating Ishita. Her subtle homophobia is surprisingly incredibly realistic. It’s represented in a way that isn’t explicitly homophobic, but rather a microaggression. A microaggression is described by a casual, minute action or phrase that communicates derogatory or aggressive attitudes towards minorities. Unfortunately, it’s a common experience to have your own identity opposed and be met with microaggressions, and Aisling is a clear example of this issue. This issue leads many people, including Humaira, to feel unaccepted and generally uncomfortable around people they were meant to be safe around.

This one example isn’t the only example of Humaira’s friends’ controversial dialogue. Later, in chapter seventeen, Humaira and Ishita are at Dee’s birthday party. Dee decides she wants to play a drinking game at her party and claims that everyone must play because it’s her party. Humaira, however, tells the group she can’t participate because of her religious beliefs.

“I’m Muslim … I don’t drink,” I say finally. There’s silence for a moment, as if this is the first time everyone in the room has realized that I’m Muslim.

“Yeah, but you’re not that kind of a Muslim,” Dee says after a beat of silence. “You don’t even wear like the…” She makes a circular motion around her head. To indicate a hijab, I guess. (p.108)

At this point, Dee has not only expressed her biphobia, but her xenophobia as well. By saying Humaira is “not that kind of a Muslim,” she is grouping Muslim people into a certain stereotype and excluding Humaira from that group because she does not fit Dee’s image of what a Muslim person looks or acts like. This, again, can be viewed as another microaggression Humaira faces due to her friends. She is, once again, being denied of her identity because she does not follow Dee’s image of what a Muslm is. To Dee, a lack of one religious practice (in this case, wearing the hijab) means that she does not follow the religion, or at least she does not follow it to the extent that other Muslim people do. It’s a subtle act that is invalidating and overall disturbing, especially to those who can relate or understand.

Showing all sides of reality is a good thing, especially in media mostly catered towards younger audiences. Jaigirdar represents every part of being queer and identifying with something that is not considered “the norm” in an area. Though it’s something important to you, it will always be scrutinized by others, whether it’s welcomed or not. The novel shows this discrimination in a way that is realistic and displeasing, but so nice to see represented. Though they face constant hardship and prejudice, the novel is still such a sweet and short read that I personally would highly recommend, especially to queer people and/or people of color.